Al-Jazari’s Marvels

Envision programmable fountains, a model of an Indian mahout (driver) who struck the half hour on his elephant’s head, or automatons in the form of servants that could offer guests a towel. These are just a few examples of the extraordinary inventions of the 12th-century Muslim inventor, Ismail al-Jazari. His work laid the groundwork for modern engineering, hydraulics, and even robotics. While some of his lavish and colorful creations were made as novelty playthings for the very wealthy, al-Jazari also made practical machines that helped everyday people, including water-drawing devices that farmers used for centuries.

A Zeal for Invention

Born in 1136 in Diyarbakır, in central-southern Turkey, Badi al-Zaman Abu al-Izz Ismail ibn al-Razzaz al-Jazari was the son of a humble craftsman. His birth came at a time of political turmoil, a result of local power struggles and the effects of the Crusades.

Al-Jazari served as an engineer in the service of the regional rulers, the Artuqids. This dynasty had once expanded its empire into Syria. However, during al-Jazari’s lifetime, Artuqid’s power came under the sway of the more powerful neighboring Zangid dynasty, and later still by the successors of the Muslim hero, Saladin.

Embed from Getty ImagesDespite the upheaval of the Crusades and the turbulent relations between different Muslim powers, life for the brilliant engineer was peacefully spent serving several Artuqid kings, for whom he designed more than a hundred ingenious devices. Unlike other practical inventors of the period, who left little record of their work, al-Jazari had a zeal for documenting his work and explaining how he built his incredible machines.

The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices

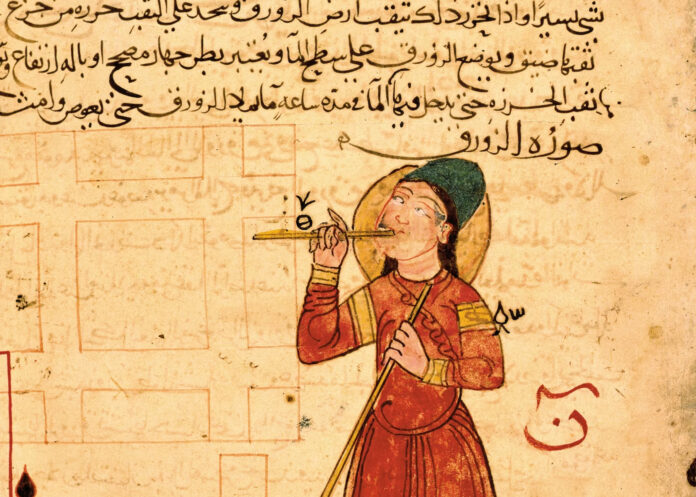

In 1206, drawing on a quarter of a century of prodigious output, he gave the world a catalog of his “matchless machines,” which is known today as The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices. Al-Jazari included meticulous diagrams and colorful illustrations to show how all the pieces fit together. Several incomplete copies of his work have survived, including one held by the Topkapi Sarayi Museum in Istanbul, Turkey, prized for its artistic detail and beauty.

Intellectual Inheritance

The Book of Knowledge is the only source of biographical information that exists on al-Jazari. The text exalts him as Badi al-Zaman (unique and unrivaled) and al-Shaykh (learned and worthy), but it also acknowledges the debt he owed to “ancient scholars and wise men.”

Al-Jazari’s inventions benefited from centuries of innovation and scholarship from previous eras, drawing on science and wisdom from ancient Greek, Indian, Persian, Chinese, and other cultures. During the rapid expansion of Islam in the seventh century, Muslim rulers took a deep interest in the knowledge of the lands they conquered. They collected manuscripts and books at the Bayt al-Hikma (House of Wisdom). This institution thrived under the Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad in the eighth and ninth centuries as a library and academy. Along with other centers, it played a fundamental role in the medieval scientific and scholarly advances during the golden age of Islam.

Influences and Inspirations

Along with philosophy, medicine, astronomy, and zoology, Muslim mechanical engineering reached exceptional heights at the hands of outstanding figures, including a trio of ninth-century Persian inventors, the Banu Musa brothers. They published many works, but al-Jazari was most likely influenced by their inventions featured in The Book of Ingenious Devices (also known as The Book of Tricks). Al-Jazari was also influenced by non-Muslim inventors such as the late third-century B.C. Apollonius of Perga is an influential geometrist whom al-Jazari credits in his work.

New Heights

Al-Jazari’s intention was not only to build on the legacy of these great inventors but to perfect it. He wrote in his foreword to The Book of Knowledge: “I found that some of the earlier scholars and sages had made devices and had described what they had made. They had not considered them completely nor had they followed the correct path for all of them… and so wavered between the true and the false.”

The machines in al-Jazari’s book were both practical and playful, from clocks to automaton vessels dispensing drinks. He designed bloodletting devices, fountains, musical automatons; water-raising machines; and machines for measuring.

One of the most famous of his devices is an enormous water clock that featured an elephant carrying his driver and a tower filled with creatures. Simple water clocks had been used in ancient Egypt and Babylonia, but al-Jazari’s intricate invention clearly expresses his ambition to perfect them.

Embed from Getty ImagesA handsome boat from which can be told the passage of an hour: In the boat is a man . . .in his right hand is a pipe, its end in his mouth . . . The boat fills and submerges in the space of one constant hour [and] the sailor plays the pipe . . . I made this device so that [a sleeper] will know from the pipe that the boat has sunk, and will wake from his doze at the sound. al-Jazari, Book of Knowledge

History’s First Robot?

One of al-Jazari’s most intriguing creations holds a special place in the annals of science history. Many consider it to be the first programmable “robot” in history. This invention, a boat with four “musicians”—a harpist, a flutist, and two drummers—was designed to play songs for entertainment. The mechanisms animating the drummers could be programmed to play different beats. While robots are entertained in al-Jazari’s time, their new abilities continue to transform our world.

Embed from Getty ImagesThese ingenious devices, however, were more than just playthings for the rich. Al-Jazari, understanding the need to impress his wealthy patrons, also created practical gadgets that eased the burden of everyday tasks. His book describes at least five machines that facilitated water drawing and irrigation, both on the farm and at home. Other highly practical machines included a crankshaft that converts linear movement into rotary movement and a means for the exact calibration of locks and other apertures.

Accessible Knowledge

The Book of Knowledge stands out not only for its content but also for its language. Unlike other inventors who deliberately used obscure language to limit their work to a small elite, al-Jazari made his work accessible to a general reader of the time. This allowed them to build some of his more practical machines. Some researchers have even described his book as a kind of “user’s manual,” reflecting al-Jazari’s interest in construction processes as much as in theory and calculations.

Embed from Getty ImagesExistence and Legacy

Al-Jazari departed this world in 1206, coinciding with the year he gifted the sultan with his Book of Knowledge. His inventions significantly influenced civic life for numerous years thereafter. Notably, a water supply system employing gears and hydraulic energy was utilized in the mosques and hospitals of Diyarbakir and Damascus. In some instances, systems inspired by his design remained operational until recent times.

His groundbreaking innovations were light-years ahead of European science. His work on conical valves—a crucial element in hydraulic engineering—was first acknowledged in Europe over two centuries later by Leonardo da Vinci, who was reportedly captivated by al-Jazari’s automatons.

In the present day, al-Jazari’s name evokes reverence among historians of science. Engineer and technology historian Donald R. Hill, the author of a landmark 1974 translation of The Book of Knowledge, stated that the significance of al-Jazari’s work “cannot be overstated.” As the pioneer of robotics, he has been referred to as the “Leonardo da Vinci of the East,” a label that is in many ways a misnomer. A more accurate comparison might be to describe Leonardo as the “al-Jazari of the West.”